Permanent outdoor

recreation areas have been around at least as long as written history. Public

areas are among  the

essential amenities any society develops, and their improvement is relatively

cheap advertising for the local monarch (large statues make great decorations). But public resort areas with amusement facilities did not appear

in Europe until the Renaissance. In England, they were called "pleasure

gardens," and they flourished from about 1550 to 1700. They first appeared

in the form of resort grounds operated by inns and taverns. They quickly proved

good for business, and became more elaborate. Vauxhall Gardens opened in

London

in 1661 covering

12 acres, and admission was free. Entertainment was provided: acrobatic acts,

fireworks, music — Mozart performed there as an 8-year-old prodigy in 1764.

Professional showmen saw the money-making potential of the concept, and began

operating them for profit.

the

essential amenities any society develops, and their improvement is relatively

cheap advertising for the local monarch (large statues make great decorations). But public resort areas with amusement facilities did not appear

in Europe until the Renaissance. In England, they were called "pleasure

gardens," and they flourished from about 1550 to 1700. They first appeared

in the form of resort grounds operated by inns and taverns. They quickly proved

good for business, and became more elaborate. Vauxhall Gardens opened in

London

in 1661 covering

12 acres, and admission was free. Entertainment was provided: acrobatic acts,

fireworks, music — Mozart performed there as an 8-year-old prodigy in 1764.

Professional showmen saw the money-making potential of the concept, and began

operating them for profit.

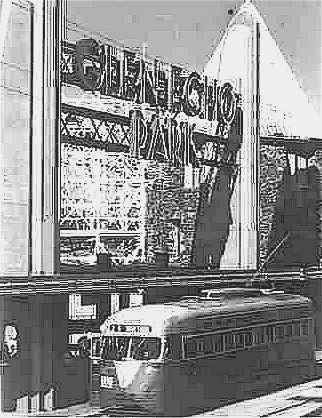

In early

America, amusement parks began as picnic grounds. Some were built by local

breweries (there's much more profit when you can sell your beer directly, rather

than through middlemen). These "beer gardens" offered the working man

an inexpensive day's relaxation for the family, including plenty of open space,

concerts, sometimes bathing, and always beer and food. Attendance was promoted

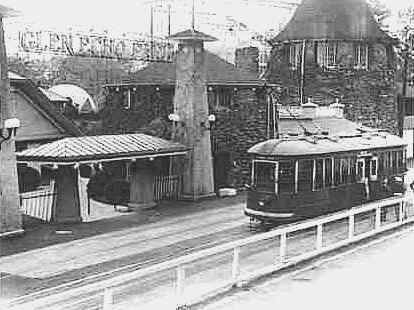

by streetcar companies and local railroad and excursion boat operators. Many

parks were developed by trolley companies. They bought their electricity at a

flat monthly rate — build amusement parks at the end of the line and you boosted weekend use at

little added expense! Before long, hundreds of such parks were built all over

the country.

man

an inexpensive day's relaxation for the family, including plenty of open space,

concerts, sometimes bathing, and always beer and food. Attendance was promoted

by streetcar companies and local railroad and excursion boat operators. Many

parks were developed by trolley companies. They bought their electricity at a

flat monthly rate — build amusement parks at the end of the line and you boosted weekend use at

little added expense! Before long, hundreds of such parks were built all over

the country.

Expositions, particularly the 1893 Chicago World's Columbian Exposition, provided another model for American amusement parks. The Chicago event was the first to concentrate rides, shows and concessions in a separate "midway." As discussed in a previous chapter, these expositions attracted teeming crowds with a multitude of lures: entertainment, education, recreation, and trade. Entrepreneurs soon learned that each attraction could boost its attendance by virtue of its proximity to every other popular feature, and that all of them together could turn profits that could never be realized by stand-alone attractions.

The story of amusement parks is largely the story of George C. Tilyou, a masterful entrepreneur whose vision created the amusement park in a form that remained unchanged until Disney created theme parks.

Coney Island

New York

City had the money and the crowds: finances to build

parks and a huge pool of working-class families looking for close and affordable

relief from the grim realities of daily life. Coney Island, a five-mile stretch

of beach at the entrance to New York Harbor where Brooklyn meets the sea, was already a popular seaside resort for the city

and environs. A pleasant and largely undeveloped spot so close to a huge

population in need of close and cheap recreation, it was destined to become home

to a succession of wonderful parks.

New York

City had the money and the crowds: finances to build

parks and a huge pool of working-class families looking for close and affordable

relief from the grim realities of daily life. Coney Island, a five-mile stretch

of beach at the entrance to New York Harbor where Brooklyn meets the sea, was already a popular seaside resort for the city

and environs. A pleasant and largely undeveloped spot so close to a huge

population in need of close and cheap recreation, it was destined to become home

to a succession of wonderful parks.

The first attractions on Coney Island were racetracks built for wealthy vacationers in 1880. A collection of attractions suited to more moderate incomes followed. Amusement rides were popular. In 1884, Lamarcus Thompson built the first amusement railroad in the world, the "Switchback Railroad." Its two wooden undulating tracks started ran down a 600-foot structure. It cost Thompson $1600 to build, but at 10¢ per ride, it took in $600-700 per day.

Young George

Tilyou,

owner of an array of single rides scattered around the island, saw the gigantic

250' Ferris wheel at the 1893 Chicago exposition. Unable to buy it (it had already been sold), he had his own 125-foot version

built. It was the most popular single attraction on Coney Island until

Captain Paul Boyton came to town.

Young George

Tilyou,

owner of an array of single rides scattered around the island, saw the gigantic

250' Ferris wheel at the 1893 Chicago exposition. Unable to buy it (it had already been sold), he had his own 125-foot version

built. It was the most popular single attraction on Coney Island until

Captain Paul Boyton came to town.

Hugely famous for

daredevil swimming feats performed in an inflatable, rubberized suit of his own

invention,

Boyton had opened Chutes Park in Chicago the previous year to take advantage of

the crowds visiting the World's Columbian Exposition. On Coney Island, Boyton opened Sea Lion Park

in 1895, enclosed by a fence and featuring a one-price

admission that entitled the visitor to enjoy all the attractions, including the

spectacular "Shoot-the-Chutes" (a water-flume ride) and the Captain's

own swimming exhibitions.

enclosed by a fence and featuring a one-price

admission that entitled the visitor to enjoy all the attractions, including the

spectacular "Shoot-the-Chutes" (a water-flume ride) and the Captain's

own swimming exhibitions.

Once Tilyou understood the idea, he ran with it. He bought and improved an 1100-foot gravity-driven mechanical ride, the "Steeplechase Horses," and opened Steeplechase Park on 15 ocean-front acres the next year. In 1902 he hired a huge illusion ride, Frederic Thompson's "A Trip to the Moon," that he had seen at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo. The next year, Thompson took the ride away to open competing Luna Park with Elmer Dundy.

Boyton's

early success, without significant competition (at first), made him reluctant to tamper with a successful and imperfectly-understood formula. With

his

"it ain't broke so don't fix it" attitude, he failed to add

or improve attractions. However, Tilyou's changing array of attractions at

Steeplechase Park, each more spectacular than the last, followed the public taste

for the new and different, a taste that turned quickly into a distinct

preference, then a demand. What pleased the paying public one year was old-hat the next. Sea

Lion Park, hopelessly out of date, fell out of favor and closed. Its 22 acres

were purchased by Thompson and Dundy, who retained only the "Chute the

Chutes" from Sea Lion and opened Luna Park on the site in 1903.

Boyton's

early success, without significant competition (at first), made him reluctant to tamper with a successful and imperfectly-understood formula. With

his

"it ain't broke so don't fix it" attitude, he failed to add

or improve attractions. However, Tilyou's changing array of attractions at

Steeplechase Park, each more spectacular than the last, followed the public taste

for the new and different, a taste that turned quickly into a distinct

preference, then a demand. What pleased the paying public one year was old-hat the next. Sea

Lion Park, hopelessly out of date, fell out of favor and closed. Its 22 acres

were purchased by Thompson and Dundy, who retained only the "Chute the

Chutes" from Sea Lion and opened Luna Park on the site in 1903.

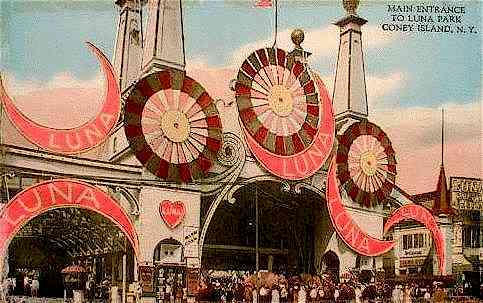

Luna Park

featured hundreds of thousands of electric lights (the technological sensation of the time),

including  nightly displays by huge searchlights mounted in its central tower, illuminating

the dozens of other fanciful towers and minarets. The influence of the

Chicago fair is reflected in the names of

many of Luna's attractions: "The Canals of Venice," "Eskimo

Village,"

"A Trip to the North Pole." There was a $1.95 one-price admission available,

but most visitors opted to pay 10¢ for most attractions, 25¢ for the

spectacular ones. Luna Park repaid its entire $700,000 cost in just six weeks.

nightly displays by huge searchlights mounted in its central tower, illuminating

the dozens of other fanciful towers and minarets. The influence of the

Chicago fair is reflected in the names of

many of Luna's attractions: "The Canals of Venice," "Eskimo

Village,"

"A Trip to the North Pole." There was a $1.95 one-price admission available,

but most visitors opted to pay 10¢ for most attractions, 25¢ for the

spectacular ones. Luna Park repaid its entire $700,000 cost in just six weeks.

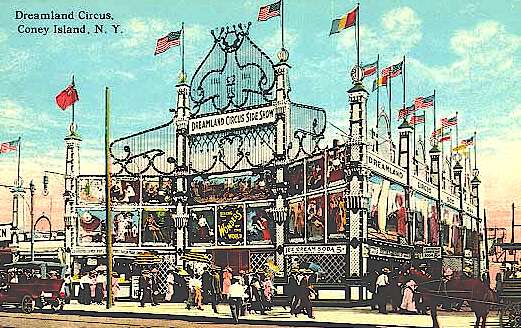

The next season, Luna was rivaled by Dreamland, whose

policy seemed to be to do everything twice as big as its competitors.

Attractions included a copy of the "Shoot the Chutes," "Fighting

the Flames," a show in which firefighters demonstrated rescues from a

six-story blazing building (two stories higher than the one premiered by Luna,

and later expanded to an entire burning city block). Dreamland affected a higher

tone than its competitors, presenting attractions with cultural and even

biblical themes. Dr. Martin Couney's "Infant Incubator" displayed

premature infants and the scientific wonders developed to help them live (of the

8,000 babies brought to Dr. Couney during his residence at Dreamland, 7500

survived).

The next season, Luna was rivaled by Dreamland, whose

policy seemed to be to do everything twice as big as its competitors.

Attractions included a copy of the "Shoot the Chutes," "Fighting

the Flames," a show in which firefighters demonstrated rescues from a

six-story blazing building (two stories higher than the one premiered by Luna,

and later expanded to an entire burning city block). Dreamland affected a higher

tone than its competitors, presenting attractions with cultural and even

biblical themes. Dr. Martin Couney's "Infant Incubator" displayed

premature infants and the scientific wonders developed to help them live (of the

8,000 babies brought to Dr. Couney during his residence at Dreamland, 7500

survived).

All three parks were built in the same style, white plaster fantasies similar to those already familiar to the public from the World's Columbian Exposition.

See

1903 Edison film of Luna Park and Steeplechase Park

THESE LINKS DON'T WORK IN THE SAMPLE PAGE,

BUT ON THE DISK THEY LEAD TO 12 MINUTES OF RARE FILM

See

a 1940 sound film of Coney Island

Samuel W.

Gumpertz came to Dreamland to build "Lilliputia," a midget city where

he housed 300 midgets for the 1904 opening season. The background midi for this

page is the sweet waltz "Meet Me Tonight in Dreamland," written for

that inaugural season. Gumpertz scoured the world for freaks, visiting Egypt,

Asia and Africa five times each  (including

two trips to Africa's unexplored center) and dozens of trips to Europe. Besides

freaks, he imported exotic humans: Filipino blowgun shooters, Algerian horsemen,

Somali warriors, "Wild Men from Borneo" who really were from Borneo

and plate-lipped Ubangi women. Never as popular as its competitors, Dreamland

burned to the ground in 1911. Gumpertz's Dreamland Circus Sideshow prospered for years thereafter in another location. Its success brought copiers,

like the World Circus Freak Show opened in 1922, followed by Hubert's Museum,

the Palace of Wonders Freak Show and more. All had fat ladies, seal boys,

pinheads, electric girls, dog-faced boys and on and on. Gumpertz left Coney Island in 1929 to manage

the Barnum & Bailey Circus.

(including

two trips to Africa's unexplored center) and dozens of trips to Europe. Besides

freaks, he imported exotic humans: Filipino blowgun shooters, Algerian horsemen,

Somali warriors, "Wild Men from Borneo" who really were from Borneo

and plate-lipped Ubangi women. Never as popular as its competitors, Dreamland

burned to the ground in 1911. Gumpertz's Dreamland Circus Sideshow prospered for years thereafter in another location. Its success brought copiers,

like the World Circus Freak Show opened in 1922, followed by Hubert's Museum,

the Palace of Wonders Freak Show and more. All had fat ladies, seal boys,

pinheads, electric girls, dog-faced boys and on and on. Gumpertz left Coney Island in 1929 to manage

the Barnum & Bailey Circus.

Steeplechase,

"The Funny Place," was every bit as good as its nickname. With rides

and attractions updated every year, the public could count on novelty,  thrills, and the delight of

seeing other people have fun. Involvement was the name of the game at

Steeplechase. At every turn (beginning with the entrance) customers were tricked

into pratfalls and comic indignities, then allowed to recover with a laugh as

they viewed others suffering the same treatment. At the "Blowhole

Theater," you could watch as patrons exiting the Steeplechase

ride passed a dwarf clown who would control air jets to blow men's hats off

and ladies' dresses upward. The spills and the thrills were all designed to

allow the odd moment of "I couldn't help it" contact with one's pretty

date … a ride on the double-saddled Steeplechase Horses wasn't safe without a

firm hug, and a tumble on the Human Roulette Wheel often brought a flash of

ankle and a friendly pile-up. Especially popular was the El Dorado carousel,

restored from the Dreamland fire and restored to its full glory of 42 feet high

and lit with 6000 lamps over three platforms in ascending tiers, each revolving

at a different speed.

thrills, and the delight of

seeing other people have fun. Involvement was the name of the game at

Steeplechase. At every turn (beginning with the entrance) customers were tricked

into pratfalls and comic indignities, then allowed to recover with a laugh as

they viewed others suffering the same treatment. At the "Blowhole

Theater," you could watch as patrons exiting the Steeplechase

ride passed a dwarf clown who would control air jets to blow men's hats off

and ladies' dresses upward. The spills and the thrills were all designed to

allow the odd moment of "I couldn't help it" contact with one's pretty

date … a ride on the double-saddled Steeplechase Horses wasn't safe without a

firm hug, and a tumble on the Human Roulette Wheel often brought a flash of

ankle and a friendly pile-up. Especially popular was the El Dorado carousel,

restored from the Dreamland fire and restored to its full glory of 42 feet high

and lit with 6000 lamps over three platforms in ascending tiers, each revolving

at a different speed.

Built of wood and plaster, the grand old parks were like well-laid fires ready to

burn. And burn they did, some repeatedly. Things were never quite the same after

the beginning of the Great War (WWI). Faced with unprecedented horrors in real

life, many patrons lost the taste for freaks, mock battles and burning blocks of

buildings. Then the  subway

to the city opened, and paradoxically, it only hastened the decline in

"business as usual." It brought millions of people to the resort, but

few of them had much money to spend. They crowded out the beaches, and their

lower-class manners made former patrons, people with a little more couth and a

little more money, uncomfortable. The people with enough money to go elsewhere

went elsewhere and took their money with them. Attractions that had prospered when

patronized by the middle class went bankrupt trying to lower prices and deliver the same services

to the poor.

subway

to the city opened, and paradoxically, it only hastened the decline in

"business as usual." It brought millions of people to the resort, but

few of them had much money to spend. They crowded out the beaches, and their

lower-class manners made former patrons, people with a little more couth and a

little more money, uncomfortable. The people with enough money to go elsewhere

went elsewhere and took their money with them. Attractions that had prospered when

patronized by the middle class went bankrupt trying to lower prices and deliver the same services

to the poor.

The Depression finished the job for most of the parks. The 1939-40 World's Fair stole away many paying customers. The sideshows were hit hard by a late 1930s ban on outside ballys. New York's notoriously hard-on-business regulations had not helped businesses weakened by years of falling attendance and neglect, followed by a "clean up the decaying area" campaign that was just a thinly-disguised attempt to make way for profitable redevelopment. Steeplechase, the first to prosper, was the last to close. Tilyou's grand vision, by then only a shadow of its former grandeur, wheezed to a halt in 1964, a victim of changing times and urban decay. Its few remaining buildings were quickly bulldozed by the land's new owner before the city could declare it a historic landmark.

Today, the island is still home to beach and boardwalk, but there is nothing as spectacular as the early amusement parks. The New York Aquarium now stands on Dreamland's site. Steeplechase's famed 250-foot Parachute Tower is the sole standing reminder of the glorious past. Ironically, the forces that killed the freak shows support one as a curiosity: "Coney Island USA" operates "Sideshows by the Seashore", partially funded by the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs.

Atlantic City

Atlantic

City, New Jersey, was a seaside resort, the eastern terminus of a railroad which

helped develop the resort. Its boardwalk dates from 1870. Starting in 1882, a

series of piers were built out over the ocean, offering all types of

entertainment for a single admission price. In 1898 the 2,000-foot Steel Pier

was built, followed in 1902 by the Million Dollar Pier, from which Houdini dove

shackled into the ocean, and on which Teddy Roosevelt campaigned for his Bull

Moose party. Top bands and entertainers attracted visitors. In the summer,

famous acts like Steel Pier's Diving Horse and a high-wire motorcycle act

swelled attendance. H.J. Heinz was so taken with the sheer numbers of people

coming to Atlantic City, people on whom advertising impressions could be made,

that in 1898 he opened Heinz Pier. The pier's unusual premise was peace and

quiet, a place to get away from the crowds.  There was a sun parlor with

reclining chairs and writing desks, free food samples (Heinz products,

of course), and a Heinz pickle pin as a parting gift. Coney Island impresario

George Tilyou built a branch of his Steeplechase Park here in Atlantic City in

1908, calling it Steeplechase Pier, where the amusements included the Sugar Bowl

Slide, the Mexican Hat Bowl, and Flying Chairs that swung riders out over the

ocean. Like Coney Island, Atlantic City enjoyed a sparkling heyday and a long

decline, until legalized gambling revitalized at least part of its tourist

trade.

There was a sun parlor with

reclining chairs and writing desks, free food samples (Heinz products,

of course), and a Heinz pickle pin as a parting gift. Coney Island impresario

George Tilyou built a branch of his Steeplechase Park here in Atlantic City in

1908, calling it Steeplechase Pier, where the amusements included the Sugar Bowl

Slide, the Mexican Hat Bowl, and Flying Chairs that swung riders out over the

ocean. Like Coney Island, Atlantic City enjoyed a sparkling heyday and a long

decline, until legalized gambling revitalized at least part of its tourist

trade.

Other parks all over the country went through charming beginnings and fantastic developments. Some have prospered continuously, others flickered and died.

Starting in 1915, new diversions (motion pictures) and new mobility (the automobile) made their mark. Many parks closed, and the Depression that began in 1929 forced the closing of many others. 2000 parks had flourished in the U.S. in 1910, but by 1934 there were fewer than 500. The same economic changes that forced circuses to adapt or die caused the park business to decline throughout World War II. Some parks failed because they did not learn what George Tilyou had always understood, and Captain Paul Boyton did not: no matter what wonders you have created, the public demands something better every year. Other parks had no room to change — the automobile would bring a vast influx of customers from greater distances, but only if they could get there on good roads and only if they found room to park. The rising value of real estate demanded more intensely profitable use of every acre in developing areas, a factor that also hit drive-in movie theaters. The postwar prosperity and the "Baby Boom" injected a little new life into a moribund industry, helped by the introduction of children's areas, "Kiddielands," spearheaded by Kennywood near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania,

Disneyland and after

In 1955, Walt Disney, already a wildly successful maker of family movies and television, marshalled his already-considerable resources: universal brand name recognition, an established stable of instantly recognizable characters, a weekly nationwide television audience, and a large parcel of unused land in Anaheim, California. He invented the "theme park," though the term was not used then: Disneyland, an environment completely under control with every element approved by the family-friendly and trusted Disney, designed for the whole family. And it was designed to be more than just a local attraction; it was meant as a destination for vacationers nationwide.

Disney was always a canny businessman. He had no need to pay for advertising … his hour-long promotional "documentaries" on Disneyland's opening aired as profitable program material!

Disneyland's image, like the rest of the Disney image, was squeaky-clean. Everything was guaranteed to be safe, spotless, entertaining and profitable. All was made in the Disney image, owned and operated without middlemen. Gone were the carnival's tawdry games, the questionable food stands, the itinerant performers. In their place were the very same hard-to-win games run by the company and staffed by earnest teenagers on summer break, and food stands run by the company. The shows were all family-friendly, with well-scrubbed college-age performers working for low wages on the premise that this experience would be good training for their future entertainment careers. The hot-to-trot girl shows remained only as a sanitized pastiche, as fresh-faced college girls performed hourly musical revues in Disney-studio costumes. The sole reminder of the ten-in-one talker was the scripted "hurry, hurry, hurry" of the youthful trained announcer twirling his fake mustache and calling everyone to his attraction — not a "Museum of Oddities" or a "Gallery of Freaks," but a barbershop quartet or a banjo band. There were no more freaks … well, there was this really big mouse. Disneyland, and later Disney World in Orlando, Florida, still attract families on the strength of an image the rest of the Disney operation seems to have abandoned (that sound you hear is Walt spinning in his grave as the next episode of Disney-distributed Ellen or one of its successors airs).

Several

companies tried to copy Disneyland's success, but none had Disney's pre-sold

combination of name recognition and (essentially free) nationwide advertising on

the weekly Disney television show. In 1961, Six Flags Over Texas opened,

followed by several other Six Flags parks across the nation, successfully establishing

themselves as regional, not national, destination parks.

Disney television show. In 1961, Six Flags Over Texas opened,

followed by several other Six Flags parks across the nation, successfully establishing

themselves as regional, not national, destination parks.

Walt Disney World, which opened in 1971, is still the largest theme park ever built. The park turned into a multi-attraction complex with the (self-styled) "visionary" EPCOT (Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow) Center, recalling the corporate advertising of a world's fair, in 1982. Subsequent additions to the complex include the world's biggest water park, interconnecting but still self-contained getaways for grownups, and one more amazing innovation. Taking as a model Universal Studios Hollywood, where studio tours added a new profit center to an existing movie/tv production facility, Disney and MGM created Disney/MGM Studios, a combined theme-park/studio. It was a stroke of show business genius! Florida's motion picture industry was already well known as the home of low-budget productions, drive-in movies and the like. Some producers, like Ivan Tors of Flipper fame, had made national entertainment careers based in Florida instead of Hollywood. The area had an established craft, technical and talent base, and was a right-to-work haven for producers looking to make shows on budgets uninflated by Hollywood and New York craft unions. The result: two big-money businesses for the price of one! Less than the price of one, if you figure in the development perks and tax breaks local governments often offer to those who bring thousands of jobs to any community.

Parks of all sorts have felt one overwhelming pressure that affects all businesses and all traditions: the public's easy boredom and demand for change. Some have successfully given the people what they want, others have not tried, or have tried and failed to find an innovation that intrigues the public.

"Things aren't the way they used to be," one old-timer has been heard to say; "and, you know what? They never were the way they used to be."

If Steeplechase and Luna and Dreamland seem to us like wonders that should never have been allowed to fade, recall the plea on the marquee of a run-down pre-renewal Times Square porn theater: "It's new until you've seen it."

Large theme parks continue to innovate, with bigger (or at least different) shows, newer rides, wilder roller coasters, and ever-higher prices, even though some are operating on a scale not much bigger than the average former local park. Many older, smaller amusement parks, like Pennsylvania's Kennywood, still find new and different ways to entertain, their charms only enhanced by their modest, comfortable size and careful preservation as reminders of bygone days.

History Section Index

1 - Early Fairs & Carnivals 2 - Expositions 3 - Freak Shows & Museums

4 - Circuses 4a - Circus Acts 4b - Clowns

5a - Wild West Shows 5b - Medicine Shows

6 - Carnivals 7 - Amusement & Theme Parks 8 - Vaudeville